Gallery History

Gallery History

The Senate Press Gallery was comparatively new when Mark Twain arrived in 1867 and made light of his new job: “If I will correspond once or twice a week from Washington, I may abuse and ridicule anybody and everybody I please.” He took aim at the Senate, too. “Senator: a person who makes laws in Washington when not doing time,” he wrote.

Among the thousands of correspondents who have passed through the gallery in more than two centuries, Twain is extraordinary for his fame beyond Capitol Hill and for the bite in his prose. But his mockery touched upon elements of tension and irreverence that have been a routine part of the relationship between the Senate and the press since the earliest days of the Republic.

Years before he became president, Thomas Jefferson wrote, “were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

But as the Senate’s presiding officer in 1800, Vice President Jefferson interrogated journalist William Duane for publishing a leak — the text of a bill that had not been debated in public. Delivering his second presidential inaugural address in the Senate chamber in 1805, the same Jefferson railed against what he called the “licentiousness” of the press. “The artillery of the press has been leveled against us,” he said.

The first Congresses had no news coverage that a modern citizen would recognize. The Senate met behind closed doors. When a viewers’ gallery was opened, reporters competed for space with members of the public. When Senate floor privileges were granted, it was only to a select few reporters, who performed more as recorders of debate than interpreters of the legislative play-by-play. Indeed, some of the most vivid stories of Senate debate in the first Congresses were written by women — non-professionals who frequented the public gallery and distributed their accounts in the form of letters to friends, family and local newspapers, according to Kate Scott, an assistant Senate historian.

Press coverage of the Senate adapted as the competition stiffened between the growing nation’s geographic regions and economic sectors. Boston merchants assigned a reporter in 1824 to cover tariff issues. Planters from Charleston, S.C. commissioned coverage of farming questions. Such writers were known as “correspondents” because their dispatches took the form of letters mailed back to their hometown papers.

In 1839, Democratic-Republican Sen. John Niles, a newspaper publisher from Connecticut, helped to kill a liberalization of press access to what is now the Old Senate Chamber, denouncing them as “miserable scribblers” who made a “miserable subsistence from their vile and dirty misrepresentations” of the Senate’s work.

But in 1841 the “Great Compromiser,” Sen. Henry Clay of Kentucky, engineered a deal to create the first official Reporters Gallery — ten front-row seats directly above the presiding officer’s rostrum. (It was another 60 years before the White House set aside space for reporters.)

“Things change any time there’s a new type of technology,” according to Senate Historian Donald A. Ritchie. Not only did the invention of the telegraph in 1844 revolutionize the speedy transmission of news copy to far-flung publications, it also gave rise to the Associated Press and other “wire” services that quickly won space and high standing in the gallery.

The AP’s chief congressional correspondent, Lawrence A. Gobright, was one of the first and most influential purveyors of objective journalism — partly as a sound business practice. Dry, terse, opinion-free reports were cheap to transmit via telegraph and marketable to publishers of any regional or political bias.

The adversarial element in Senate-press relations resurfaced periodically. After New York Herald reporter John Nugent published the secret treaty that ended the Mexican War in 1848, the Senate ordered the sergeant-at-arms to arrest him. Nugent was confined in a committee room for several weeks — under fairly benign circumstances and with daily outings for meals. He never consented to name his sources. It was not the last failed effort to dry up Senate leaks by placing reporters under a form of house arrest.

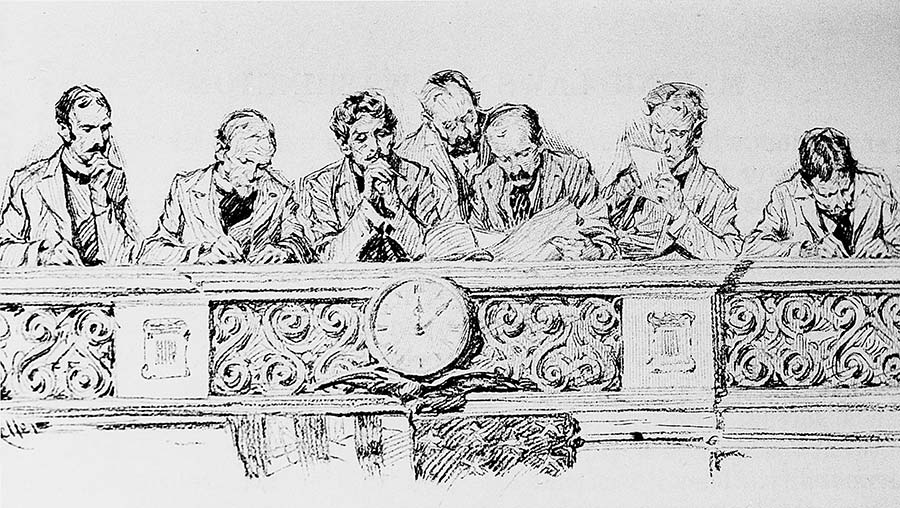

Horace Greeley, Frederick Douglass and Mark Twain were among the famous writers to work in the gallery. They covered Washington during years when the congressional press corps grew rapidly. Twain – who “double-dipped” as a Senate staffer and correspondent – satirized the relaxed ethics of the Senate in the post-Civil War era. (Left and right: Senate Historical Office; center: Library of Congress)

A frequent Senate correspondent (and, briefly, congressman) during the 1840s was Horace Greeley. The anti-slavery crusader published the leading Whig (and, later, Republican) organ, the New York Tribune.

With the Capitol’s expansion in 1859 came the Senate’s move into its current chamber — under the gaze of a large gallery of press seats on the north wall. Beyond were offices that featured a press lobby, a telegraph station and the floral-patterned Minton tiles from England that correspondents still tread upon today.

For many years it was the Senate’s presiding officer, the vice-president, who ruled on which reporters were granted access to the press gallery. The Senate Rules Committee later assumed this power.

The sudden expansion of the congressional press corps during the Civil War gave way to decades of “large-scale and rapid postwar industrialization, of financial wheeling and dealing, and of considerable economic and political corruption,” the late Sen. Robert C. Byrd, Democrat of West Virginia, said in his speeches on the Senate’s history.

In this era, the Senate correspondent-staffer was a perfectly respectable figure, as epitomized by a little-remembered leader of the gallery Ben Perley Poore of the Boston Journal and the Providence Journal. Both were Republican papers, the latter edited and partly owned by Rhode Island Sen. Henry B. Anthony, who made Poore a powerful Senate clerk and publisher of official documents. Poore wrote a detailed memoir of the gallery of his era and founded a publication that has lived on, the Congressional Directory.

Perhaps Mark Twain owed some of his cynicism to the fact that, like many of his peers, he was a double-dipper. He covered the Senate for newspapers from San Francisco and Chicago, and he drew a Senate salary as secretary to a Republican senator from Nevada. Other correspondents had even more brazen conflicts of interest, moonlighting as lobbyists. Inevitably, some reporters were drawn into scandal. The House expelled or investigated reporters who served the Colt revolver company, a Wisconsin land concern and a West Coast steamship line.

Some commentators charged that lackadaisical coverage of the Senate and House implicated the press in the Credit Mobilier railroad bribery scandal of the 1870s.

The whiff of corruption “soured Senate-press relations,” said historian Ritchie.

The Senate and House experimented with various reforms, finally settling on a press proposal in 1877 to police gallery independence from within. The House was first to recognize the representative body that steers the press galleries to this day, the Standing Committee of Correspondents. The Senate followed suit in 1884, granting the correspondents committee the power to accredit journalists for membership in both galleries after screening them for conflict of interest.

“I don’t know of any other government that allows the journalists to head up the system of handing out press passes,” said Ritchie. Over the years, other federal institutions, including the Supreme Court and several executive agencies, have made membership in the congressional press galleries a prerequisite for their own press passes.

The gallery’s unusual, hybrid chain of command has endured. The taxpayers own the premises and pay the professional staff under the aegis of the Senate sergeant-at-arms. But the volunteer Standing Committee wields real power under the rules of both houses, to establish and enforce the codes of the Senate and House Press Galleries and to oversee hiring and staff.

The Senate Press Gallery got its first official superintendent in 1897. James D. Preston, who began the staff’s practice of tracking legislation and tallying votes, served until 1931.

The Standing Committee has played a leading role in the long and uneasy effort to open Senate proceedings that stayed behind closed doors well into the 20th Century.

It was pressure from the chief AP correspondent Paul Mallon that precipitated the Senate’s decision, to open up most of its secret “executive sessions” for votes on nominations and treaties in 1929. Sen. Robert M. LaFollette, Jr., Republican of Wisconsin, defended Mallon in a Senate speech, arguing that it was plainly senators themselves who had long been responsible for the leaks of routine but secret proceedings.

Left: Members of the Senate press corps in the late 1930s. The busts of vice-presidents, including John Adams (left) and Thomas Jefferson (right) signify their role as presiding officers of the Senate. Both men would lash out at press coverage of their presidencies. Right, the press gallery is seen, upper left, in a 1939 photograph of the Senate in session. (Senate Historical Office)

After World War II, the ferment in the larger society spurred the press to focus upon its own issues of access — the obstacles that women had traditionally faced in covering the Senate and the outright exclusion of blacks for much of the gallery’s history. Nominally, the rationale for barring black reporters was that the accredited dailies assigned no black reporters to the gallery. There was a vigorous black press in many cities, but it was largely confined to weekly newspapers.

In 1947, the Senate Rules Committee ordered the Senate Press Gallery to admit a black reporter, Louis R. Lautier, deeming that his weekly, the Atlanta World, also served as a news service.

The telegraph had become a pretext for sexual discrimination in the Senate Gallery in the 19th Century. The Standing Committee decreed early in its rule that members had to be correspondents who filed stories via telegraph. The handful of active female reporters on Capitol Hill still corresponded principally by letter. Women who filed by telegraph did win credentials, but the newspapers themselves maintained barriers to the good hard-news assignments.

It took the intervention of World War II for women to get the best stories on Capitol Hill, Mary Hornaday of the Christian Science Monitor recalled. The reason was practical: male reporters went overseas to cover the front.

The all-male press corps has gone the way of the spittoon and the fedora hat. (Left: Senate Historical Office; right: Tom Williams, Roll Call)

The gallery’s most notable changes in recent years have come with advances in some technologies, sometimes at the cost of declines in others.

With the proliferation of cable television outlets, the Senate embraced live television coverage of its debates in 1986 (several years later than the House). Habits changed in the press corps, as in offices across Capitol Hill. Attendance declined inside the gallery during debates; the coverage of C-SPAN2 on TV monitors became a permanent part of the gallery’s background.

The advent of the Internet presented the Standing Committee with the dilemma of how – and whether – to accredit news organizations that had no connection to daily newspapers. As with earlier breakthroughs in technology, Ritchie said, the admission of Web-based reporters to the Senate Press Gallery looks inevitable in retrospect.

The gallery accredited an on-line reporter as early as 1980. In 1996, the gallery adopted standards that treated Web-based reporters essentially the same as it treated print reporters.

By the end of the new century’s first decade, the Senate Press Gallery had undergone one of its periodic facelifts. Among other changes, wireless capacity was improved and the number of telephone booths was reduced to five. Today’s gallery members are less likely to take calls in the old-fashioned phone booths than they are to duck in with their cellular phones to make calls in privacy.

The bins for paper press releases from senators fell into disuse and were removed.

The population of the gallery has shifted dramatically. The membership of regional correspondents for smaller newspapers – once a large fraction of the gallery’s regulars – has declined dramatically with the fortunes of their industry.

Concurrently, the membership of correspondents for Internet publications has soared.

Over the years, many senators have paid tribute to the Senate Press Gallery’s service to an informed citizenry and to the constitutional freedom of the press.

But as Senator Byrd noted in the 1980s, the Senate and the Senate Press Gallery have always found ways to coexist in their adversarial relationship. Perhaps, Byrd suggested, that is owing to the “symbiotic” nature of their dealings.

“The truth is that the Senate needs the press corps to keep the public informed about our legislative business,” Senator Byrd said in one of his addresses on Senate history. “No amount of speeches, newsletters or personal correspondence could ever equal the impact of their daily reporting, although we are not always pleased by the results.”

A Senate majority leader of the 1980s and 1990s saw another enduring phenomenon in the day-to-day habits of the press.

“Sometimes members of the media can be seen hanging over the gallery desks trying to get a glimpse of the roll call tally or attempting to read the lips of senators telling tales in the well,” Sen. George Mitchell, Democrat of Maine, said in a speech to the Senate on the gallery’s 150th anniversary in 1991. “No matter what the hour of the issue, the press is here to monitor and report to the American people our words and deeds.”

Left: Democratic Senators Dick Durbin of Illinois (background) and Chuck Schumer of New York take questions in the Senate Press Gallery during the Congress. Right: The late Democratic Senators Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia and Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts, shown here at a “pen-and-pad” session in the gallery, served together in the Senate for 47 years.

Directors/Superintendents of the Senate Press Gallery

1886-1888: John L. Reade

1888-1898: Clifford Warden

1898-1932: James D. Preston

1932-1941: William J. Collins

1941-1955: Harold R. Beckley

1955-1973: Joseph E. Wills

1973-1981: Don C. Womack

1981-1983: Sandra H. Hays

1983-2002: Robert E. Petersen, Jr.

2002-2013: S. Joseph Keenan

2013-2023: Laura E. Lytle

2024-present: Laura E. Reed